Archives

NASCAR's First 200 mph Lap:

The Story Behind Cotton Owens' Dodge Daytona and the Legendary Hemi that Powered Buddy Baker to a New Record

Courtesy of RM Auctions

"Win on Sunday, sell on Monday"

"Win on Sunday, sell on Monday" was never more important than in the years that crossed the intersection of the Sixties and the Seventies. These were the days of all-out, no holds barred, performance. Ford, Chrysler and GM deployed teams of engineers, drivers, mechanics to devise technical advantages and finesse the rules makers.In the late Sixties the focus was on engines and power. Chrysler, GM and Ford deployed fabulous, exotic engines – the porcupine head Chevy, the Dodge and Plymouth 426 Wedge, Ford’s threatened sohc 427 – while NASCAR, NHRA, USAC and an alphabet soup of other sanctioning bodies and promoters fiddled with rules to try to keep one brand from running off with everything, keep the cars looking like something fans could buy in the showroom on Monday and keep one step ahead of the imaginative ways cagey guys like Dale Inman, Smokey Yunick and Bud Moore came up with to gain an advantage over their competition.The most egregious example of manufacturers’ specialization to meet NASCAR and USAC production requirement is Chrysler’s 1963 creation of the second generation Hemi engine and then putting it into the wildest automobiles ever offered to the general public, the 1969 Dodge Charger Daytona and the 1970 Plymouth Road Runner Superbird.

The Hemi

Chrysler was getting hammered on the NASCAR ovals and the NHRA strips in the early Sixties. The story goes, too, that Chrysler Chairman Lynn Townsend’s teenage sons were coming back from Woodward Avenue and giving their dad the word that his company’s products were nowhere. In late 1962 Townsend gave the go-ahead to create a second generation Hemi. To minimize development time and costs it was based on the basic dimensions of the 413/426 wedge block so it could be machined on existing tooling.Working with a nearly impossibly short deadline, the 1964 Daytona 500, Chrysler’s program was a success, with Hemi powered Plymouths taking the top three places and five of the top ten. Richard Petty’s pole-winning speed for the 500 was more than 13 mph faster than his pace in 1963. NASCAR banned the Hemis in 1965, then relented. Ford withdrew in 1966 citing the Hemi’s advantage, then came back when NASCAR allowed them dual 4-barrel carbs. Chrysler came back in 1967, dominating the season in his Plymouth. Ford responded in 1968 and 1969 with the Holman-Moody Fords driven by David Pearson.

The Winged Warriors

The Winged Warriors

The dominance of Ford was more than Chrysler could countenance. Rather than creating limited production aerodynamic bodies (like the fastback Charger) Chrysler turned to its design studios with the objective of creating a production car that was aerodynamic on the track but also stylish and handsome on the showroom floor. The new 1968 Charger hardtop was a beautiful, sleek, design but it wasn’t aerodynamic enough. Something more was needed. It was the Charger Daytona 500, with flush grille and extended fastback rear glass worth a minimum of five mph. It also prompted Ford to unveil its counterparts, the Torino Talladega and Cyclone Spoiler. They completely dominated the Charger at Daytona in 1969. The Chrysler designers went back to the drawing boards and reviewed their data from wind tunnel testing. Two teams of Chrysler designers came up with essentially the same conclusion: replace the Charger’s ring bumper with an extended aerodynamic nose cone and a low front spoiler.It worked, but it also exacerbated the nose lift problem. Conventional wisdom would counter that with a rear deck spoiler but in practice it would have to be so large most if not all of the advantage created by the nose would be lost. Working simultaneously in the wind tunnel and trying promising changes on the Chelsea test track the solution was found: a wing mounted on tall pylons at the very back of the rear deck. The height of the wing was set not by aerodynamics but by the simple realization that it had to clear the rear deck lid when it was opened. Other design features were added. Running with the nose down helped reduce lift but caused the front wheels to rub the fender tops at speed. They cut out the offending fender areas and added bumps for a little more clearance. Excessive turbulence at the windshield corners was tamed with wind deflectors on the a-pillars. It was outrageous, but it worked. Planned as a 1970 model, a bomb dropped on the engineering staff when the introduction date was pushed up to September, the date of the 500 mile race at the brand new superspeedway at Talladega, Alabama. Track testing at Chelsea continued in parallel with production of the 500 copies needed to meet NASCAR’s requirements. On July 27 Charlie Glotzbach lapped the Chelsea oval at 204 mph. Then testing revealed that the Talladega surface and the record speeds were fatiguing the tires. Many top drivers and teams boycotted the race including Chrysler’s test driver, Charlie Glotzbach, although a Daytona driven by Richard Brickhouse won at a carefully controlled reduced speed. In 1970 the Charger Daytona and its new stablemate from Plymouth, the Road Runner Superbird came into their own and were nearly unbeatable, winning 38 of the season’s 48 races. One of the leaders was the Dodge Daytona entered by Cotton Owens and driven by

Buddy Baker.

Cotton Owens grew up with NASCAR from the earliest days driving modifieds. In 1959 he finished second to Lee Petty in the season points with 22 top ten finishes in 37 races, including winning the Daytona Beach and Road race in Pontiac’s first NASCAR victory. In 1960 he won his qualifying race at the Daytona Speedway, the first NASCAR race carried on live television. He was one of the team owners consulted by Chrysler in 1962 before development began on the new Hemi, telling Chrysler, “I told them if they’d go back to the

Hemi engine I’d do it. The Hemi builds more horsepower than any other engine…. Dodge promised if I’d sign I’d get a Hemi, so I signed under those conditions,” and became part of the effort from the very beginning. ("All Around The Track", Anne B. Jones and Rex White, McFarland 2007. In 1969 Owens teamed up with Buddy Baker, son of NASCAR pioneer Buck Baker from Darlington’s Rebel 400 on. The pair scored an impressive series of results including a run of eight straight top ten finishes at the end of the season. Owens and Baker started 1970 off strong, starting their Daytona qualifying race from the pole and finishing second to

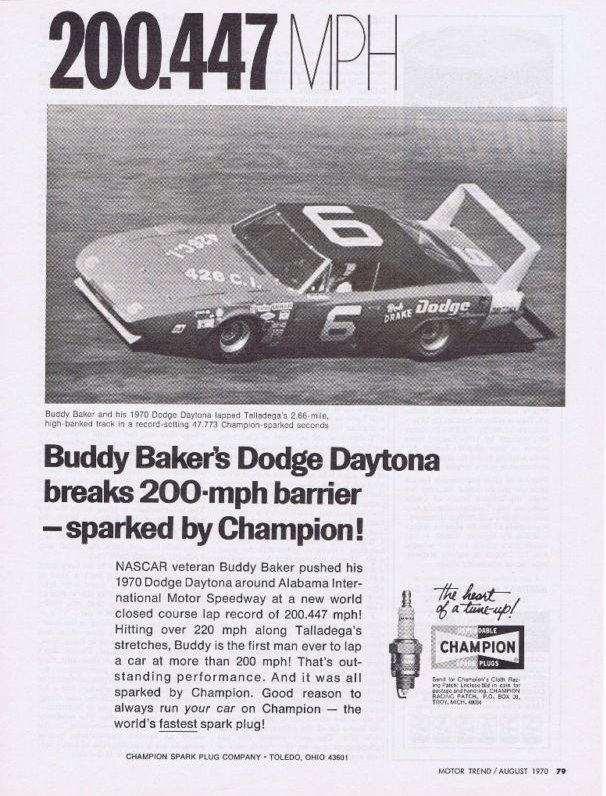

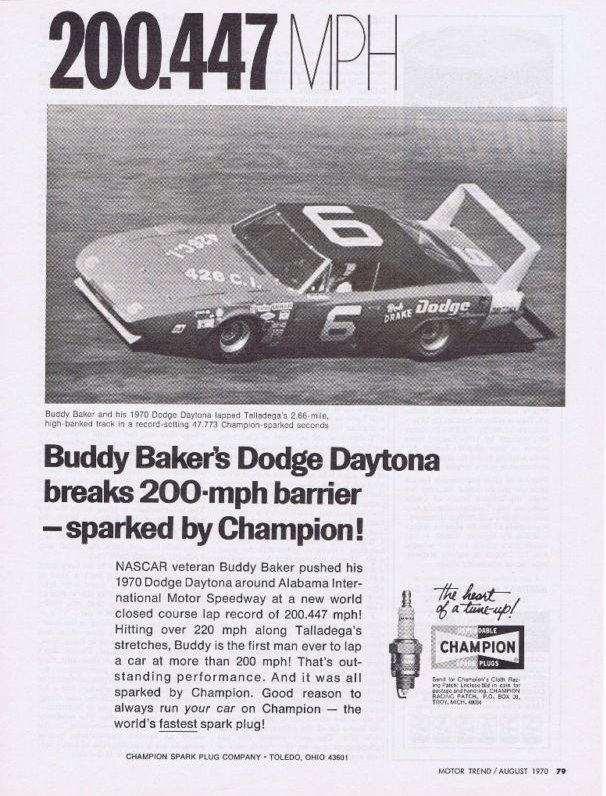

Charlie Glotzbach but an ignition problem put them out of the 500 itself. Problems dogged them at Rockingham and Atlanta but Baker in the #6 Charger Daytona were the class of the field in the Alabama 500 at Talladega on April 12, leading 101 laps until a spin and a fire put them out of the race. It was in this race as Baker was leading the field that he accomplished the feat which will forever make this car famous: recording the first NASCAR race lap at over 200 mph. The accomplishment was heavily promoted by Chrysler, even more than the continuing successes of the Chargers and Superbirds, because it was a singular accomplishment. It led inevitably to another of Bill France’s competition building innovations, the carburetor restrictor plate, which has forever limited superspeedway speeds to well below 200 mph.

Baker drove Owens’ #6 Charger Daytona to a second place finish in the Firecracker 400 at Daytona in July, to fourth at Atlanta in August, sixth in Michigan on August 16, fifth at the Talladega 500 August 23. With this car Baker then won the Southern 500 at Darlington on September 7 by a lap over second place Bobby Isaac. On the same weekend Cotton Owens was inducted into the National Motorsports Press Association Hall of Fame at Darlington.By now NASCAR had announced the rules for 1971. They limited the aerodynamically bodied cars to just 305 cubic inches displacement, spelling the end of the brief, brilliant career of the Dodge Charger Daytona and its counterparts from Plymouth, Ford and Mercury. When this car was in an accident at Charlotte on October 11 (after qualifying third and leading twenty laps) Owens rebuilt it as a display car to participate in Dodge’s national promotion of the 200-mph lap. In rebuilding it, he made the changes to the interior, doors and windows that are visible today. It was displayed by Dodge at Cobo Hall in Detroit in January 1971 then was brought back home to Spartanburg before being taken to Darlington – NASCAR’s first superspeedway – and put on display in the museum there. It remained on display for the next generation, an example of a famed, golden era in American racing.

On July 19, 2005 it was released from the museum and brought once again back to Cotton Owens Garage in Spartanburg, South Carolina. Cotton himself put in new oil, pulled the plugs and oiled the cylinders, disconnected the distributor, put in a new battery and cranked the engine to pump oil pressure. With new plugs and the ignition reconnected he hooked a line from a gas can to the fuel pump and squirted some gas into the carb.She fired on the second try.Since then Cotton has done further work to tune, clean and prepare the car. It was acquired directly from Cotton Owens in 2005 by the present owner who has had it carefully and consistently maintained in his museum by professional staff. Other than the mechanical work to bring it back to operation after nearly thirty-five years on display it is exactly as it was after Darlington and Charlotte in 1970. Its Hemi roars with the sound of a legend: the first NASCAR Grand National Cup series automobile to turn a race lap at over 200 mph. It is a feat which will never again be experienced, not only because it is the first, but also because safety concerns will never again see a Cup car lapping at speeds like that in a race attended by the public. It is one of the landmarks of American racing, built and tuned by a legendary driver-mechanic-team owner, extensively authenticated by him, driven by one of the stars of NASCAR Buddy Baker and powered by the incomparable Race Hemi. It is one of few NASCAR Grand National series cars from this epic era to survive untouched and carefully preserved. Exactly as raced, it is a reminder of a time when racing and racers admitted to few limitations in speed, ingenuity, determination and courage.